Article appears in the Fall 2025 Ranch Record; written by Sue Hancock Jones

After touring with Annie in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, Indian chief Sitting Bull became Annie’s “adopted father” and gave her the name “Little Sure Shot.”

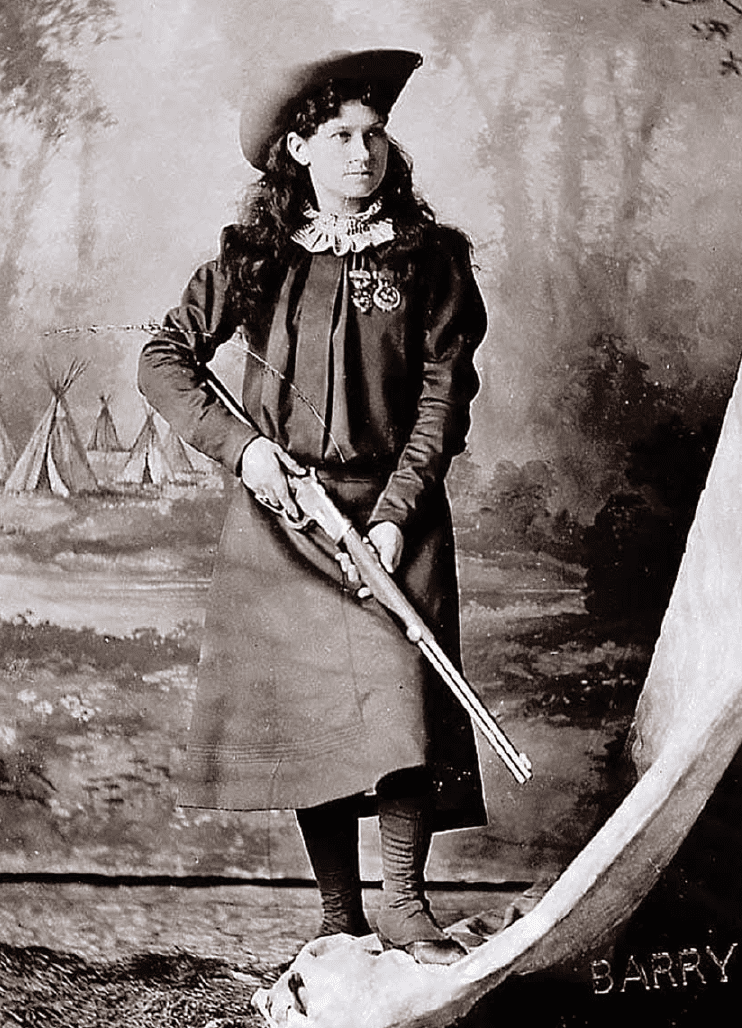

Annie Oakley’s fame throughout America has endured for a century beyond her death in 1926.

Not knowing Annie Oakley’s name was almost impossible in 20th-century America. Barbara Stanwyck played Oakley in the 1935 film Annie Oakley. Ethel Merman played Annie in the 1946 Irving Berlin Broadway musical Annie Get Your Gun. From 1950 to 1999, the role of Annie was played by famous Hollywood stars including Betty Hutton, Mary Martin, Gail Davis, Geraldine Chaplin, Jamie Lee Curtis, Reba McEntire, and Bernadette Peters. Marvel Comics even published 11 issues of an Annie Oakley comic book.

Although Annie’s name has lived on into the 21st century, some details may have been lost in translation. The older generation remembers the Annie Oakley name, but not everyone remembers why she is famous. Was she a rodeo cowgirl? Did she sing? No, but Annie Oakley was the first American woman—the first—to be a superstar. She was the Taylor Swift of her era. While it wasn’t her vocals that carried her notoriety, it was her gift of sharpshooting that made her a legend throughout the world in a male-dominated sport.

After Oakley joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in 1885, she became a legendary figure of the American West even though she was born, resided, and died in Ohio. During her marriage she lived in New Jersey, Maryland, New York, Florida, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Virginia, and Ohio, but no record exists of Annie ever having visited, lived, or performed in the American West. That being said, her family was one of the early settlers of western Ohio in 1860, that may have been the frontier.

Perhaps the closest Annie ever got to the American West was her close friendship with Sitting Bull, the most distinguished and famous Indian leader of his generation. Eight years after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the Lakota Sioux leader attended one of Oakley’s performances in St. Paul, Minn., in March 1884. Enthralled by her skills and personality, he arranged a meeting where he called her “Watanya Cicilla,” or “Little Sure Shot.”

In addition to giving her a nickname that followed Oakley the rest of her life, Sitting Bull later traveled with the Wild West Show and adopted Annie not only as a member of the Lakota tribe, but he also asked her to take the place of his daughter who died shortly after the Battle of the Little Bighorn. His daughter would have been the same age as Annie. Oakley took the honor seriously and wrote of Sitting Bull as her “adopted father.”

POVERTY IN CHILDHOOD

The death of Annie’s father impoverished the family and resulted in Annie learning to kill an animal with a head shot to allow its meat to be preserved for dinner.

Born August 13, 1860, in a log cabin in Darke County, Ohio, Annie was the sixth of Jacob and Susan Moses’ nine children and the fifth of the seven surviving children. Her name was Phoebe Ann Moses, but her sisters called her Annie.

Annie’s father was driving a team of horses into town to buy supplies when he got caught in the blizzard of 1865. He became an invalid as a result of hypothermia and died of pneumonia in 1866 when Annie was six years old.

Historians have questioned whether the family’s last name was Moses, Moscy, or Mozce, but the gravestones of Annie’s two nephews that sit beside her gravesite have the name Moses. They were a Quaker family who had migrated from Pennsylvania to a rented farm in a rural county on the Ohio-Indiana border.

While her sisters played with dolls, Annie at an early age tagged along with her father as he hunted and trapped in the woods. She trapped birds and small animals to help provide food for the family, but she showed an extraordinary talent for marksmanship.

“I was 8 years old when I made my first shot,” she recalled, “and I still consider it one of the best shots I ever made.” Steadying an old muzzle-loading rifle on a porch rail, she picked off a squirrel sitting on a fence in her front yard with a head shot to allow its meat to be preserved for dinner.

Annie’s mother remarried and had another daughter before her second husband died suddenly. Unable to support the family, her mother sent Annie and her sister Sarah Ellen to the Darke County Infirmary—the county poor house—when Annie was 9. According to her autobiography, she was put in the care of the infirmary superintendent, Samuel Crawford Edington. His wife Nancy taught Annie to sew and decorate.

Eventually Annie was “bound out” in the spring of 1870 to a local family to help care for their infant son in return for the false promise of 50 cents per week and an education. As a 10-year-old, Annie spent two years in near slavery to the family and endured mental and physical abuse. On one occasion the wife put Annie outside in freezing temperatures without shoes as a punishment for having fallen asleep over some darning. Annie never divulged the name of the family but always referred to them as “the wolves.” She ran away and returned to her mother’s home when she was 15.

When Annie returned home, she helped support the family. Her shooting and trapping not only put food on the table but also eventually allowed her mother to pay off the $200 mortgage on the family house through the money Annie earned shooting quail and pheasants in the head to keep the edible portions of the birds entirely free of buckshot. Annie sold the game she hunted to a local Greenville grocery store that supplied hotels and restaurants in Cincinnati.

LITTLE SURE SHOT

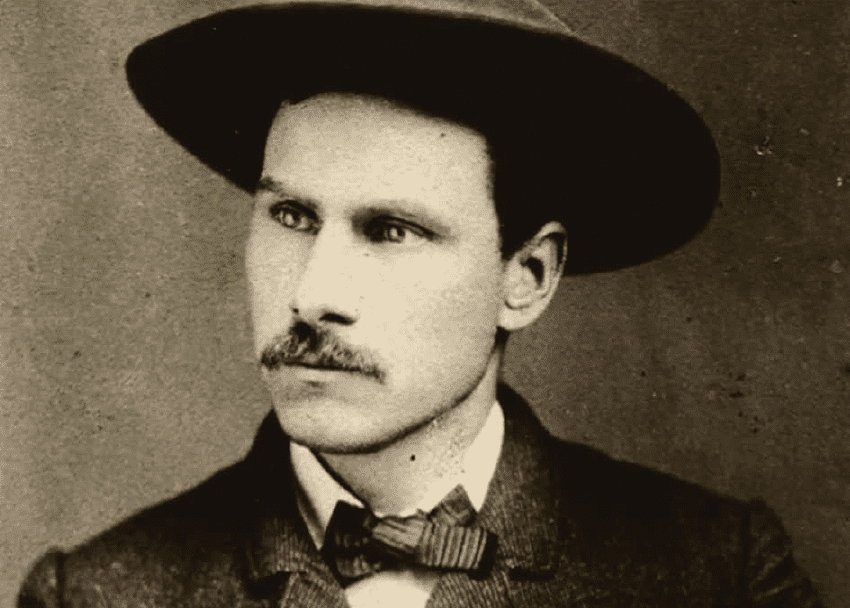

Annie was 15 when she participated in a shooting match with professional exhibition shooter Frank E. Butler. He lost the match, fell in love with his opponent and put his career on a backburner to manager her career.

Many years before Sitting Bull named Annie “Little Sure Shot,” the 15-year-old teenager left home and lived with her married sister near Cincinnati. Numerous accounts exist of what happened next, but the Annie Oakley Center Foundation, Inc., reports that Cincinnati hotelkeeper Jack Frost knew Annie’s reputation as a shooter and arranged a match with a professional exhibition shooter named Frank E. Butler.

The match was run according to the regular rules of trap shooting. Frank shot 25 of 25 birds, and Annie killed all 25 birds. Frank later would say he had lost as soon as he saw the pretty and shy 15-year-old Annie. She was five feet tall and weighed 110 pounds. He wasn’t expecting to fall in love with his opponent.

Depending on which account you believe, they married in 1876 or 1882. Annie always said 1876, but a certificate on file with the Archives of Ontario, Registration Number 49594, reports that Butler and Oakley were wed on June 20, 1882, in Windsor, Ontario. Other sources say the marriage took place on August 23, 1876, in Cincinnati, but no record certificate confirms that date. A possible reason for the contradictory dates may be that Butler’s divorce from his first wife was not final in 1876.

Annie and Frank Butler initially lived in Cincinnati. Her stage name—Oakley—was adopted when she and Frank began performing together. Some historians believe her famous last name was taken from the neighborhood of Oakley where they lived in Cincinnati.

Annie traveled with Frank on his sharpshooter’s show with John Graham. When Graham got sick and Oakley stood in for him, she was an instant hit. That was the moment Annie became a permanent part of the act. To Frank’s credit, he immediately realized his wife had star quality, so he put his own career on a backburner to manage her career.

A RISING SUPERSTAR

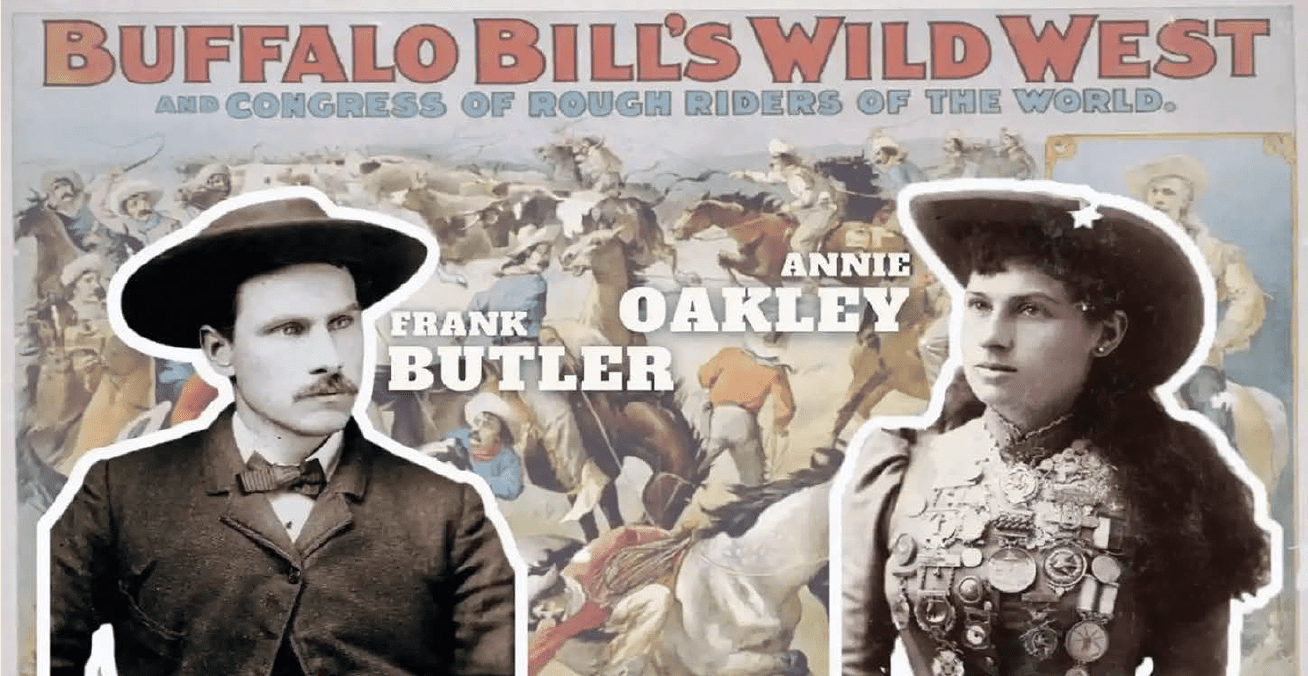

The Butlers joined the Sells Brothers Circus in 1884, but Annie did not shoot her way to everlasting fame until after William “Buffalo Bill” Cody put her and Frank on his payroll in 1885. Buffalo Bill refused to hire Oakley for his Wild West show after their first encounter because he already had an expert marksman.

In late 1884 a steamboat carrying the show’s performers sank in the Mississippi River. The passengers made it off safely, but the sharpshooter’s prized firearms had a watery demise. This created an opening for Oakley in 1885.

Annie and Frank toured with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show for 17 years, typically performing in 130 town s a year in America. In her first European tour in 1887, Annie performed for Queen Victoria and gave 300 European performances in six months. The show returned to Europe for more tours from 1889 to 1892.

From 1885 to 1901, Frank and Annie were fixtures on the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show. Annie quickly became the star attraction while Frank became the manager and wrote articles and press releases. Annie said the financial part was always in Frank’s hands.

Audiences were enthralled that Annie could shoot off the end of a cigarette held in her husband’s lips, hit the thin edge of a playing card from 30 paces, and shoot distant targets while looking into a mirror. When playing cards were tossed into the air, she could shoot holes through the cards before they landed.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show traveled to London in 1887 as part of the American Exhibition meant to coincide with Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. They gave several special performances for the royal family. During the performance for Queen Victoria, the queen rose and bowed deeply when the American flag came into the arena. It was the first time a British monarch had saluted the American flag, and the members of the show roared their approval. The show stayed for six months and gave more than 300 performances that helped Annie hone her showmanship.

In 1889 the Wild West Show toured Europe beginning with the Exposition Universelle in Paris. They toured southern France, Spain, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Germany before returning to America in 1890. The show returned to Europe for two more tours in 1891 and 1892, including another performance for Queen Victoria in 1892.

Annie became a celebrity, earning more than any other employee in the Wild West Show except Buffalo Bill. After they returned from Europe, Annie and Frank bought a house in Nutley, N.J., to have a place to live between tours. Each tour typically took them to 130 towns.

Buffalo Bill, 15 of his Indians, and Annie Oakley were filmed by Thomas Edison in 1894 in Edison’s Black Maria Studio in West Orange, N.J. The films were turned into nickelodeons. The public could go to Kinetoscope parlors, pay a nickel, and see Annie shoot.

In 1901 the Wild West Show members were traveling in North Carolina to their final performance of the season in Danville, Va. Because of a misunderstanding at the switching station, the second train – the one Annie and Frank were on – ran head-first into a southbound train. After the train wreck, her hair reportedly turned white overnight. Whether it was because of this accident or the nearly 20 years of touring, the 41-year-old sharpshooter retired from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

Annie tried acting and appeared in a play called The Western Girl in 1902, where she wore a wig to conceal her white hair. She also began giving shooting lessons at exclusive shooting clubs. Frank became a representative of the Union Metallic Cartridge Co., a position that allowed the couple to continue their shooting exhibitions while endorsing the company’s products.

In 1912 the couple began building a house in Cambridge, Md. The roof was designed so Annie could step out onto the roof and shoot game off the Choptank River. They spent the rest of their life in that house and at resorts in North Carolina and Florida. Annie performed in a benefit show on Long Island in 1922 and was rumored to be making a comeback. In November at the age of 62, she was in a car accident in Florida and fractured her hip and ankle.

As her health began to decline over the next four years, she and Frank returned to her roots in Ohio. When Annie was ill in 1925, she stayed in Dayton with her sister, Emily Patterson. Annie’s great great aunt, Irene Black, shared a family story of Annie’s appointment to have breakfast with Will Rogers.

“HE came to the Patterson home,” Black said, “and Annie was waiting in her bedroom because she was too weak to get out of bed. Mrs. Patterson dressed her in all pink. Breakfast was served to the two famous people.

“When Will Rogers came down the stairs, he had tears running down his face. Mr. Rogers told Mrs. Patterson, ‘My mother told me that if I say my prayers every night, I’ll see angels, but I never thought I’d see one on this earth.'”

On Nov. 3, 1926, Annie Oakley died of pernicious anemia at the age of 66. Frank mourned so deeply that he stopped eating and died 18 days later on Nov. 21.

Annie eventually moved back to Ohio to be closer to family. She died at age 66 and Frank died three weeks later. Their ashes are buried at Brock Cemetery near Greenville, Ohio, next to two of Annie’s family members.